JACKSONVILLE, Fla -- – One of the more heated recent topics on Hurricane Ian was the landfall forecasts and their accuracy.

So, how accurate were Ian’s landfall forecasts? It’s a bit complex.

Recommended Videos

The First Warning

The National Hurricane Center, and many meteorologists around the country, began to get concerned about possible impacts on Florida during the third week of September.

The Tropical Weather Outlook, a product produced by the National Hurricane Center, indicated on Mon., Sept. 19 that a tropical wave approaching the Lesser Antilles had a low chance of development.

One day later, on Tues., Sept. 20, the National Hurricane Center upgraded the wave to a high chance of development, due to the organization presented on satellite.

At this point, some long-range computer models were indicating a northward trek of the tropical system, possibly toward Florida.

The First Forecast Cone

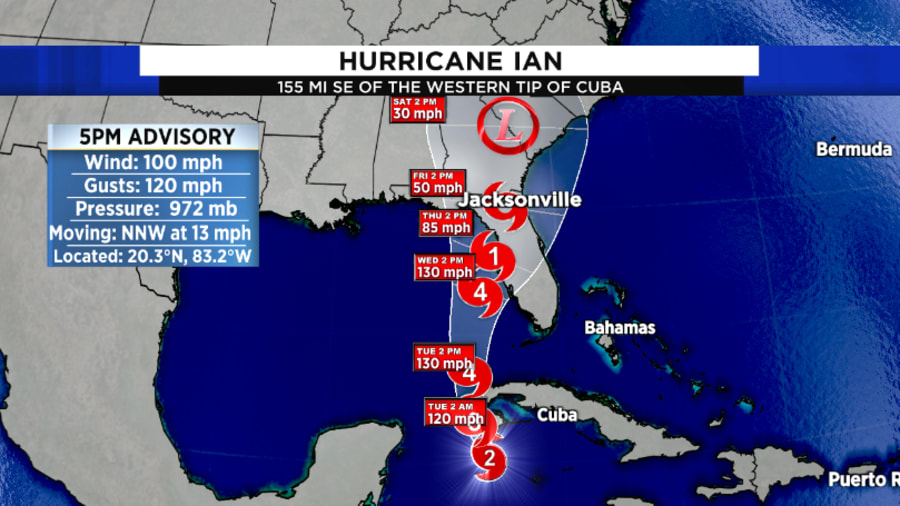

The tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Nine on Fri., Sept. 23. The very first advisory from the National Hurricane Center had the depression becoming a hurricane near the Cayman Islands, with a possible landfall in Southwest Florida.

In fact, the center of the cone five days out was within 15 miles of the eventual U.S. landfall point.

Unfortunately from there, the main global models had a very difficult time resolving the storm.

“Model Madness”

While the model issues will be researched for years to come, one of the key issues was how the models were handling a developing trough north of Florida.

The American computer model, named the GFS, continued for the next several days presenting varying solutions to the west of the initial forecast cone.

In fact, at one point during the weekend of Sept. 24-25, one run of the model had a landfall in southern Louisiana.

The other major model, the European or Euro, was much more consistent. But even it had continuity issues.

The Euro model also began to drift slightly westward over the course of the next several days as well.

This forced the National Hurricane Center to begin jogging the forecast cone north.

By Sunday morning, the official forecast cone had moved north and westward, with a possible landfall near St. Marks, in Florida’s Big Bend region.

However, the forecast cone was a compromise between the GFS and the Euro, and other major hurricane models.

The Hurricane Center noted this in a discussion Sunday morning:

“The UKMET and ECMWF models continue to hold firm along the eastern side of the guidance and show a track into west-central Florida, while the GFS and HWRF remain on the western side, taking the Ian into the central or western Florida panhandle. The updated NHC track continues to split these differences. . .”

National Hurricane Center Sun., Sept. 25 5 a.m. Forecast Discussion

The Shift Back South

The forecast models continued their disagreements into Mon. Sept 26, but a more southerly track was being identified. That day, the forecast cone was shifted southward, with center of the cone near Tampa Bay.

At this point, what was becoming apparent was the threat of significant storm surge along the Gulf coast. A Storm Surge Warning was issued for much of the west coast of Florida, with a possible storm surge of 4-7 feet forecasted.

By Tues., Sept. 27, the forecast models were still in disagreement. This was unusual considering landfall would likely occur within 48-72 hours.

It was becoming highly likely on that Tuesday that landfall was to occur south of Tampa Bay, from the Suncoast down to Southwest Florida.

On Wed., Sept. 28, Ian became a rapidly intensifying Category 4 major hurricane. A landfall in Southwest Florida had become imminent, and Ian slammed into Cayo Costa in coastal Lee Co. at 3:05 p.m.

The Reliable Forecast Cone

While the computer models were jumping around on the track of the storm, the official forecast cone from the National Hurricane was actually extremely accurate.

Despite the movement of the cone northward into the Big Bend, the landfall point in western Lee Co. was never removed from the cone.

Many people believe the forecast cone is based on impacts, but the forecast cone is actually the area with which the center may reside. The cone is actually the range of uncertainty in the prediction.

The goal of the National Hurricane Center is for the center of circulation to reside in the entire cone 2/3 of the time.

With Ian, the center always resided in the first forecast cone and subsequent forecast cones as well.

It is also important to note with the plethora of forecast models now available to the general public, meteorologists still must analyze the data and make their own analysis.

Just like a doctor makes a diagnosis based on tests and lab results, meteorologists make predictions based on data from forecast models, hurricane hunter aircraft, and remote sensing data.

“Raw” computer model data can lead to confusion among the public and give an impression a storm is moving away when oftentimes that is not the case.

Every storm is different, and with Ian, the computer models did vary wildly and the forecast cone did lift north and westward.

However, Southwest Florida residents did have several days’ notice that a hurricane landfall was very possible in their area during the last week of September.

We will continue to talk more about Ian and why the storm was so bad in the coming days and weeks.